The Mystery

In 2016 my father was diagnosed with a crippling disease. He asked me to clear out his loft since he could no longer access it. There I found records which had belonged to my mother's father. He had died in 1984 when I was still a boy so I had little knowledge.

Many of the records were pre-war 78s which were bound in albums. Each side only recorded a few minutes so many sides were needed to cover classical symphonies. Other records were post-war 33rpm LP vinyl records, both in Mono and pioneering Stereo. These high fidelity records each covered entire symphonies featuring renowned orchestral performers on famous labels such as Decca, Columbia and HMV.

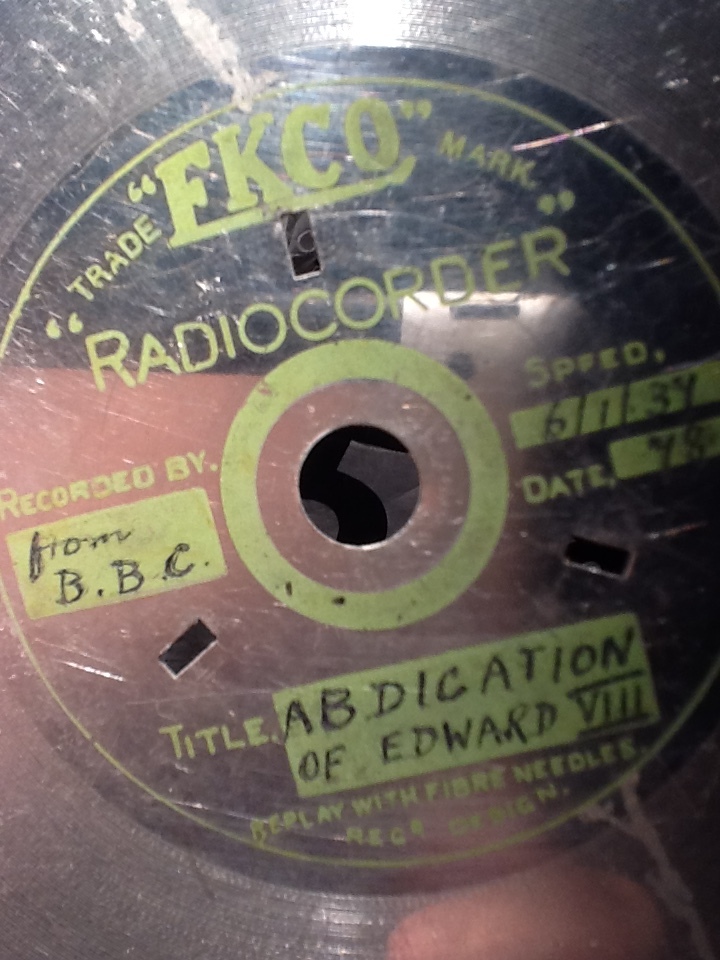

But a number of metal records defeated easy identification. Below is a slideshow of a few (just click on or touch image). These have been taken from a sizeable stack that require listing. Labels indicate who made the records, when they were made and their content. The metal is noticeably light and slippery. Even where labels are worn the writing has been etched on the surface beneath, indicating the metal's softness.

That metal is aluminium and the internet reveals how this was once used in the early 1930s for recording prior to lacquers. Note these metal discs have nothing to do the "negative" electroplated surfaces of wax recordings used to produce commercial records. The internet also reveals how rare aluminium discs are. Demand for the metal during WW2 is thought to have destroyed the vast bulk. There is almost no public information. Even the British Sound Library's recording manual makes little reference.

One record above is dated 25th December 1937 and appears to contain George VIs first Xmas message to the nation. This makes it almost 80 years old. There is likely no other "off air" recording of that speech in the world today. The speech was officially recorded and issued to the public on a commercial shellac record. It can be heard on the British Sound Library website under oral history. George VIs later radio broadcasts were considered vital to wartime morale and his story has been widely publicised in the film "The King's Speech".

Relevantly there is an early scene in the film where he is "home recorded" by his therapist. The unwilling prince orates while wearing headphones which deafen him with music. Although the new technology is embraced by the therapist it clearly intimidates the future king. Feeling humiliated he refuses to listen to the record and leaves. He reluctantly accepts it "as a souvenir" as he walks out the door. Later he plays the record alone and is stupified by the power of his own disembodied voice. His relationship with both technology and therapist starts to change.

The record in these critical scenes appears lacquered. Yet if these events really did happen might the King's first recording been like my grandfather's? Might a humble disc like his have empowered a prince and changed the course of history?

The answer to those questions is yes ... and no!

Yes my grandfather cut his discs in a similar way to that seen in the film. But no, that recording machine is described as a "Silvertone, the latest thing from America". This used "acetate" discs which comprised of an aluminium base lacquered with nitrocellulose. These would have produced less noise and taken less recording effort but would have been less durable too. Over time the lacquer would delaminate and nitrocellulose is highly flammable. On the other hand, although aluminium is reactive, it rapidly forms a protective oxide coating in air. This might explain why my grandfather's recordings appear to have endured the decades.

The device owned by my grandfather was not American. It was almost certainly the British-made "EKCO Radiocorder". The internet reveals one advertised for sale below in 2013. Whether any aluminium discs were present was unclear. The manufacturer EKCO Ltd was based in Southend where I am told my grandparents took a day trip in 1933 just after they were married. Coincidentally this electronics company suffered a setback that year when fire ravaged its research laboratories but its fortunes later recovered during WW2 and the demand for RADAR.

So how did my grandfather use this kit?

It hardly compares to the integrated Silvertone unit shown in the "King's Speech". No doubt the necessary information is contained in the small book depicted. Furthermore one of my grandfather's discs is labelled "How to Record". Maybe these sources might be recoverable and provide insight.

In the meantime The Investigation below attempts to confirm the Radiocorder's operation using an alternative method. This is "reverse engineering" by inspection. It is technical and may seem obscure. But it concludes with a specification of the "pick-up" and technique required for achieving playback.

The Investigation

So below then is my diagram of how the components labelled A to F may have been connected and what they did. For the playback of recordings the kit would have used a valve amplifier, speaker and turntable. For recording it would also have needed either a radio antenna plus tuning circuits or a microphone. Additional microphone "pick-up" connections and perhaps an amplifier output transformer may also have been needed.

Two channels are shown, channel 1 for playback and channel 2 for recording. Recording arm (B) and playback arm (D) are separately mounted beyond the turntable edge. When not in use the playback arm is supported on the crutch which may be part visible in the upper compartment of the sales box. When not in use the recording arm was simply removed from its mount (A).

The playback arm is electrically connected to A which provides a range of accessible electrical connection points to the amp. Points 1 and 2 cover the two channels (with perhaps 3 a common earth). No doubt more wiring was used than depicted since the technology preceded the general use of standard co-axial cable and jack connections.

In recording mode (with channel 2 selected by toggle switch G) the output from the valve amp is channelled to both the speaker and the recording arm via box E. This box includes a switch to turn on/off the input to the recording arm and start/stop the modulations of the "cutter". In playback mode (with channel 1 selected by G) the output from the playback arm is channelled to the input to the valve amp via box F. This box includes a potentiometer providing volume control.

The final component in the diagram is the silvery box C (see sales box). This would have contained a needle held by a moving coil armature inside a static magnetic field (possibly permanent or energised using a field coil). This device was either a modulating "cutter" or a "pick-up" depending on the arm it was connected to and whether recording or playing.

That mode would also have determined the needle used and the mechanical action of the box. Sharpened hard steel needles would have been used for "cutting" and soft fibre needles (thorn or bamboo) used for playing. A packet of steel needles and a sharpening device may be visible in the lower compartments of the sales box.

During play the pivoting arm swung along a conventional horizontal arc allowing the needle to stay in the groove, the contact tracking force determined by the weight of the box. During recording the box would have tracked inward along the supporting arm on a lead screw driven by the rotating turntable via spur gearwheels and a rubber rimmed idler wheel resting on the inner non-recording surface of the disc. This would have allowed the needle to score a spiral groove into the aluminium surface at a pitch determined by the spur gear ratios and the screw thread.

A turntable platter featured male elevations which mated with the triangulation of slots observable on the discs. This engagement prevented any slippage caused by the friction between needle and groove. That friction would not have been significant during play (although it can result in skating) but during recording when the aluminium was required to yield to the steel "cutting" needle. This friction depends on tracking force and rotational velocity. The velocity would have reduced as the cutting needle tracked inwards. But it is unclear how the corresponding tracking force behaved or was even applied. Perhaps the recording arm pivoted axially against the force of a coil spring? The precise mechanism is unclear.

Understanding the Radiocorder's operation allows the recorded surface to be understood. This is vital if play is to be reliably achieved and wear or damage minimised. These discs were not stamped and pressed in a mould like commercial records nor was a groove cut in the sense that material was removed. Instead a hard steel needle made a shallow laterally-modulated depression on the surface of the soft aluminium while simultaneously raising ridges on either side. The late British Sound Library's sound archivist Peter Copeland refers to such discs as being embossed (see later).

This has adverse implications for play for a couple of reasons. Firstly this is how a slice might appear if it were put under a microscope.

This shows that any "pick-up" may not settle in the modulated groove but instead occupy the "silent" gap between ridges. That issue may be addressed using a stylus with a large tip radius (such as the Ortofon 2M 78). This will ensure a snug fit in the wide groove. Certainly a microgroove stylus should be avoided since it would likely waggle about and dislodge.

But using a modern precision stylus with its hard jewelled tip introduces a second issue, that of damaging the soft aluminium. Back in the 1930s that was addressed with a soft fibre needle. Making and using bamboo needles was practical when you could fit them to the bulky sound boxes of the period. But using them is not practical when attempting to play and digitise recordings with modern equipment using a compact magnetic cartridge designed for a precision stylus.

This would appear to leave no option for digitisation. But while an old steel needle in a hefty sound box (which guessing would weigh about 250 grams) would destroy these records, a modern magnetic cartridge mounted on a counter-balanced tone arm only applies a tracking force of a few grams. Furthermore all recording media (whether vinyl, shellac or otherwise) are worn by contact with jewelled styli so this is always a concern that simply requires managing whatever the medium.

Peter Copeland also makes this encouraging remark on page 55 of his 340 page (and reputedly unfinished) manual (while usefully advocating diamond as the preferred jewel).

"diamonds can play embossed aluminium discs; sapphire is a crystalline type of aluminium oxide, which can form an affinity with the sheet aluminium with mutual destruction" (Note the Ortofon 2M 78 is diamond tipped and spherically shaped which also minimises wear)

So in summary the "right" stylus may limit damage to acceptable levels, albeit at the tail-end of what may be considered normal where careful compromise must be struck between tracking force, wear and reliable "pick-up". Random variables such as corrosion, dirt, damage and wear must inevitably disrupt a finely struck balance resulting in jumping and skating. So tracking instability has to be expected with the need for continual intervention, interruption and adjustment to restore balance. Digitisation is likely to involve generating multiple samples, requiring extensive editing and reassembly into continuous audio tracks. That approach may be frustrating and time consuming but should be achievable.

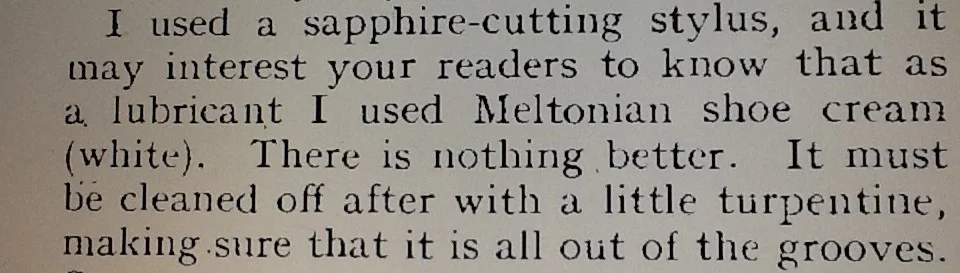

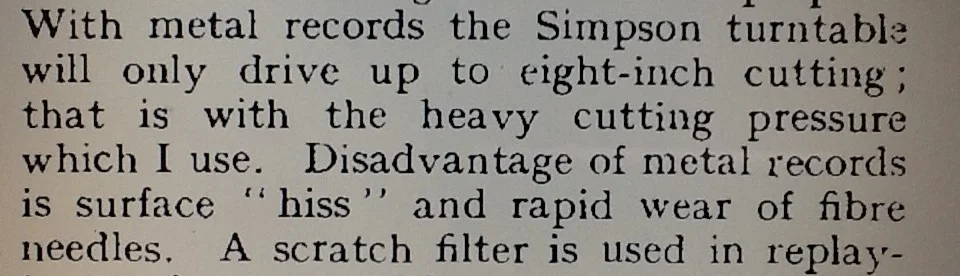

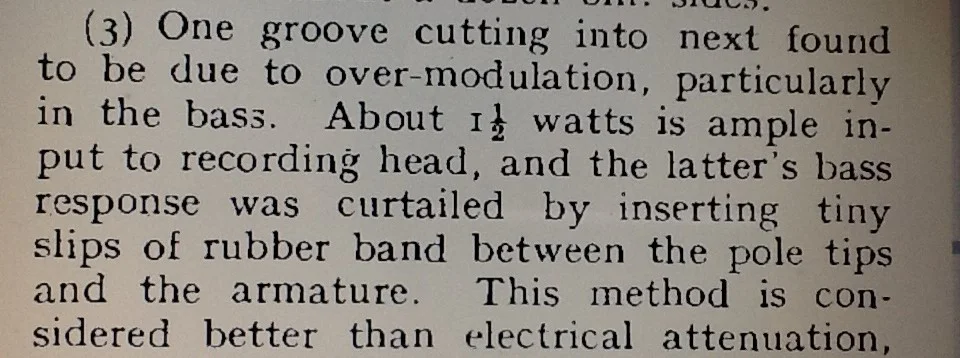

In any case whatever the frustrations of playing these discs, the excerpts below from "Wireless World" indicate that cutting them was far more trying. It is a tribute to my grandfather's skill and patience that he cut so many.